International friendship day

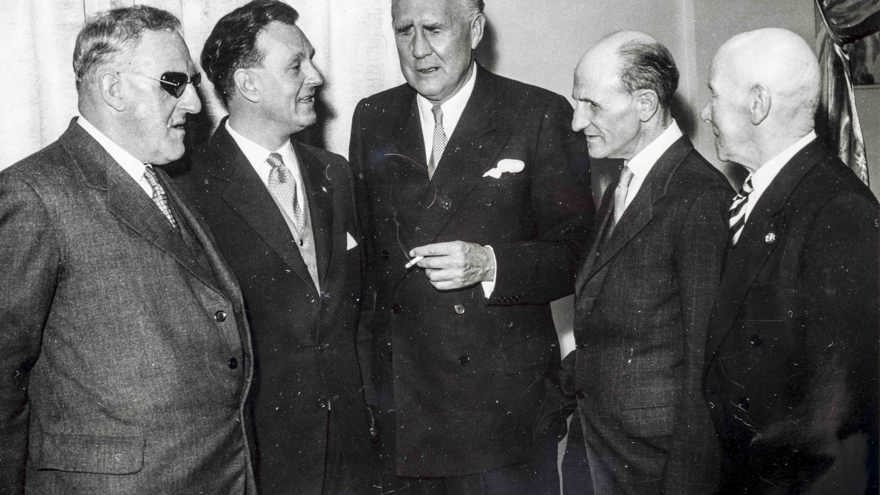

On this international friendship day, we’re publishing an excerpt from an article written by our then Chairman Lord Fraser. The original article was published in our member’s magazine Review in July 1951.

Whilst the article is 68 years old, a lot of it is still relevant today. Times may have changed, but the importance of friendships remains the same.

Friendship and blindness

Friendship is a tender plan which can only grow out of understanding and common interest, but even this delicate relationship must be thought about and to some extent planned. I do not mean to suggest that you can calculate a friendship in advance or plan to make one, but I do mean that you cannot enjoy the company of your friends, or to do the things with them that are agreeable to both of you, unless you think about them and to some extent arrange them beforehand. It is a handicap to some blind people whom I know not to realise this, or to be too shy to give it a thought and make it part of their way of life.

If you can see, you can enter a group freely, taking advantage of the right opportunity to begin a conversation with the person with whom you want to speak. Or you can watch for the conclusion of a rubber of bridge or a game of bowls and join in at the appropriate time, or catch your friend’s eye, or be available so that you are brought in and become one of the group. If you enter a club or a pub and you can see, you can stand for a moment or two at the door and look around at the various groups talking, playing or drinking, and make up your mind which to join.

Socialising as a blind person

If you are blind and enter a room in similar circumstances, you start with the great disadvantage of not knowing who is there, of not being able to enter easily into the company of the others, and unless you have thought about this matter and developed the art of overcoming your own particular difficulty, you must either be left out altogether or be drawn into a group that is incompatible, unfriendly, awkward or boring.

I cannot pretend to have become very expert at overcoming these difficulties, but a long period of public life in which I have had to meet all kinds of people and as far as possible, mix with them, has taught me some lessons which I pass on for what they are worth.

Friendship without barriers

The most important lesson of all is not to be shy about your blindness or embarrassed by your own difficulties. If you are either of these, then you will most certainly communicate the shyness or the embarrassment to others. The first requisite is to assume that in normal circumstances most people will be glad to see you, talk to you, and to bring you in as part of their group.

This is not always true and depends to some extent upon not taking advantage of any kindness that is shown to you. For if you become a bore or a trouble to the others, if you hold up the activity which they want to undertake, or if you do it in a way that spoils their fun, then the best will in the world will not overcome the reluctance with which they greet your approach. In general, however, most people will welcome you. Blindness of itself is no bar to good conversation.

A cause of difficulty that often presents itself is that of not knowing to whom you are talking. I have found in this connection that the simplest way of dealing with it is to ask a direct question. You will enter a group and someone will say, “Hallo, Joe.” Nine times out of ten you will know who it is and conversation will flow freely, but at the tenth time you will be at a loss to know who is speaking to you. If you let that moment pass in the hope that further information will solve the mystery, you will probably be sunk.

As often as not you will find conversation drying up or you will make some remark that is inappropriate. The best thing to do is to say immediately, “Who is this?,” or “Who is speaking to me?” Even if, in itself, the question causes some embarrassment (and if often does because people are very shy about saying their own names), it will nevertheless clear the air and enable you to adjust yourself to the person you are with.

Next I would say, never fail to ask the person you are with to do the thing that you want. By this I do not mean impose any task upon your friend or acquaintance. Sometimes, however, the other person wants to help but does not know how to do it. My advice is to leave him in no doubt but tell him exactly what you want done and the way you want it done. You will find then that a happy and agreeable friendship follows.

If it is a question of walking together, tell the person quietly on which side you prefer to walk and whether you wish to hold his or her arm or vice versa. If it is a question of being read to, explain what you want to read and how you want it read. The assumption that you should make is that the person wants to do the job as well as possible and that any awkwardness is cause by lack of knowledge rather than by lack of willingness.

More news

Founder's Awards recognise our blind veterans

25 Oct 2023 • Wales

"Living statue” takes over Manchester Piccadilly

19 Oct 2023 • North England

Standing down our iconic Brighton centre

3 Aug 2023 • South England

Sign up for email updates

We would love to send you updates about our work and how you can support us.

You can change your contact preferences at any time by calling us on 0300 111 2233 or emailing us. See our privacy policy for more details.